In the bustling streets of Mumbai, a 27-year-old Chartered Accountant named Rishi Pramod Ganatra encountered a moment of profound realization. Weighing 182 kilograms, the turning point arrived at a local rickshaw stand. The driver refused him service, fearing the vehicle would collapse under the physical strain. This moment of friction catalyzed a three-and-a-half-year journey. Rishi ultimately shed 80 kilograms by transitioning to a disciplined calorie deficit. His story is not an anomaly. It is a testament to the fundamental principles of thermodynamics. By mastering caloric intake and energy expenditure, he transformed from a sedentary student into a high-energy professional.

The struggle Rishi faced is shared by over 40% of adults in the United States. Many urban professionals navigate the transition from athletic youth to sedentary adulthood with difficulty. For most, weight gain is a slow accumulation driven by professional stress and hyper-palatable, ultra-processed foods. However, the path to reversal lies in a precise, quantified approach to weight loss. This strategy prioritizes nutritional density over mere restriction.

Defining the Calorie Deficit: The First Law of Thermodynamics

A calorie deficit exists when you consume fewer calories than your body expends to maintain its current mass. In scientific terms, calories are units of energy derived from food and beverages. Energy expenditure represents the total energy used for vital functions and movement. When a shortfall is created, the body must tap into its endogenous fuel stores. It utilizes glycogen and adipose tissue to compensate for the missing energy.

This process is rooted in energy metabolism. The body constantly adjusts to intake levels. If you consistently consume a surplus, the body stores the excess as fat. If you maintain a deficit, the body utilizes that stored energy. While simple in theory, the execution is complicated by metabolic adaptation. This is a survival mechanism where the body slows its basal metabolic rate (BMR) to conserve energy.

The Four Pillars of Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE)

To understand how to lose weight, you must first master the TDEE calculator concept. Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE) is the sum of all calories burned in a 24-hour period. This metric is more accurate than looking at exercise alone. It encompasses both involuntary and voluntary energy use. For those looking for a personalized starting point, the Diet Dekho intake form provides a structured way to begin this assessment (https://dietdekho.com/form/).

The first pillar is the Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR). This accounts for 60% to 75% of daily energy use. This energy keeps the “lights on” in the body, powering the heart, lungs, and brain during rest. The second pillar is the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). It accounts for approximately 10% of expenditure. This is the energy required to digest nutrients. Protein has a higher TEF than carbohydrates or fats. The third and fourth pillars are Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT) and Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT).

| Component of TDEE | Percentage of Expenditure | Primary Function |

| Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) | 60% – 75% | Life-sustaining involuntary functions |

| Non-Exercise Activity (NEAT) | 15% – 30% | Walking, fidgeting, daily chores |

| Thermic Effect of Food (TEF) | ~10% | Digestion and nutrient absorption |

| Exercise Activity (EAT) | 5% – 10% | Structured workouts and sports |

Quantitative Assessment: The Mathematics of Maintenance

Calculating the precise calories needed for weight loss requires validated mathematical models. Modern researchers suggest the Mifflin-St Jeor formula provides a reliable estimate for contemporary populations. The formula varies based on biological sex due to inherent differences in muscle mass.

For a biological male, the BMR formula is:

BMR=(10 × weight in kg)+(6.25 × height in cm)−(5 × age in years)+5

For a biological female, the formula is:

BMR=(10 × weight in kg)+(6.25 × height in cm)−(5 × age in years)−161

Once the BMR is established, multiply it by a Physical Activity Level (PAL) to determine the TDEE. This multiplier adjusts the baseline energy needs to reflect your lifestyle. It ranges from sedentary office work to elite athletic training.

Calibrating the Activity Multiplier for Accuracy

The most common error in a fat loss journey is the overestimation of physical activity. This leads to an inflated TDEE and a failure to reach a true deficit. A sedentary individual with a desk job should use a multiplier of 1.2. Conversely, a moderately active person who exercises three to five times a week would use a multiplier of 1.55.

| Activity Category | PAL Multiplier | Description of Lifestyle |

| Sedentary | 1.2 | Desk job, little to no intentional exercise |

| Lightly Active | 1.375 | Light exercise 1–3 days per week |

| Moderately Active | 1.55 | Moderate exercise 3–5 days per week |

| Very Active | 1.725 | Hard exercise 6–7 days per week |

After identifying the TDEE, a deficit is created by subtracting calories. A reduction of 500 calories per day is often cited as the gold standard. It theoretically results in the loss of one pound of body weight per week. However, energy balance is dynamic. As weight is lost, the TDEE naturally decreases. This requires periodic recalculations to avoid plateaus.

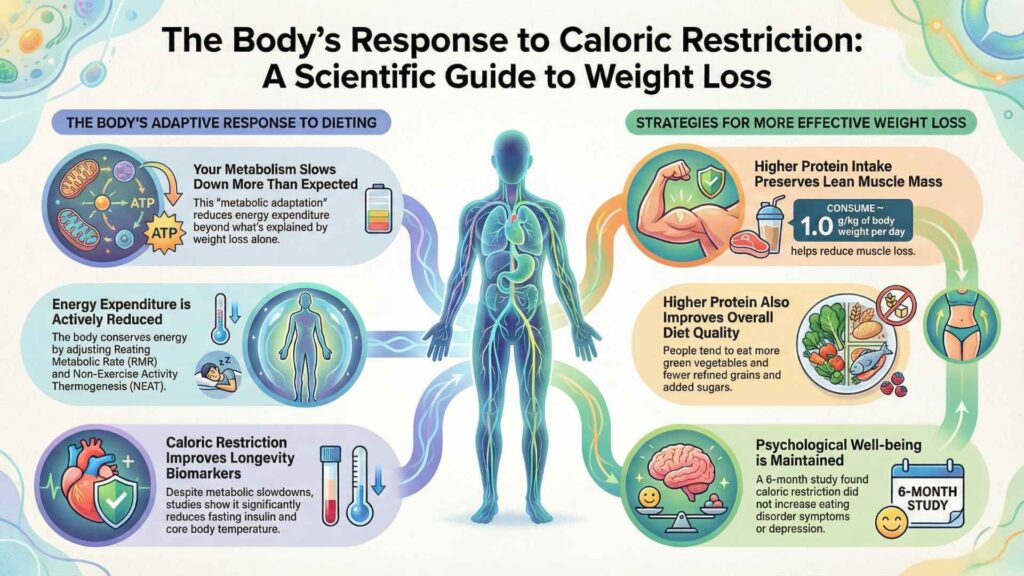

Metabolism and the Adaptive Response to Restriction

Metabolism is not a static engine. It is a responsive biological system that prioritizes survival. When a calorie deficit is introduced, the body undergoes metabolic adaptation. During this phase, the body becomes more efficient at utilizing energy. This means it burns fewer calories to perform the same amount of work.

This adaptation can reduce the BMR by as much as 15%. If the deficit is too aggressive, the body may begin to break down muscle mass for fuel. Since muscle tissue is metabolically expensive, its loss further reduces the daily caloric burn. This creates a cycle where weight loss becomes increasingly difficult. For detailed metabolic insights, researchers point to guides from Harvard Health Publishing (https://hsph.harvard.edu).

Calorie Deficit for Women: Hormonal and Cyclical Nuances

For women, creating a caloric deficit is tied to the menstrual cycle and life stages. During the luteal phase, a woman’s resting energy expenditure can increase by 2.5% to 11.5%. This metabolic surge is often accompanied by increased appetite and cravings. This makes maintaining a deficit particularly challenging.

Extreme energy restriction in active women can lead to functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA). This condition reduces estrogen exposure, which is critical for bone density and heart health. Research indicates that an energy deficit exceeding 22% of total needs is a predictor of menstrual disturbances. Therefore, weight loss strategies for women must be moderate and supportive of hormonal health.

The Role of PCOS and Metabolic Resistance

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) represents a specific challenge where insulin resistance makes traditional weight loss less effective. Dr. Mahira Menghani reversed her PCOS symptoms and shed 42 kilograms in eight months. She adopted a nutrient-dense, ovo-lacto vegetarian diet. Her journey highlights that for those with hormonal imbalances, calorie quality is vital. She focused on protein-rich tofu, paneer, and eggs.

Success often involves mindful eating. She replaced deep-fried foods with air-fried or steamed alternatives. By managing insulin levels through low-glycemic choices, individuals can bypass metabolic resistance. This underscores the importance of a personalized approach to the fat loss journey.

Nutritional Density: Quality vs. Quantity in Energy Intake

While the requirement for weight loss is a negative energy balance, the source of calories impacts adherence. A report from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) emphasizes that ultra-processed foods drive the obesity epidemic. These foods are hyper-palatable and calorie-dense but sparse in fiber and essential nutrients.

Participants eating an ultra-processed diet consumed approximately 500 more calories per day than those on an unprocessed diet. They reported identical levels of hunger and fullness. This suggests that the body’s appetite regulation is easily bypassed by industrial food processing. Sustainable success requires healthy eating centered on whole foods. Fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins trigger the brain’s satiety signals more effectively.

High Protein Low Calorie Snacks in the Indian Context

Snacking is often where many fat loss journeys falter. However, it can be a strategic tool for managing hunger. In India, traditional snacks can be adapted to be calorie-conscious. Choosing snacks high in protein and fiber, such as roasted makhana, provides a steady release of energy.

| Indian Snack | Caloric Value | Primary Nutritional Benefit |

| Roasted Makhana (1 cup) | 68 kcal | High fiber, low glycemic index |

| Paneer Tikka (100g) | 144 kcal | High protein and calcium |

| Boiled Chana Salad | ~110 kcal | Plant-based protein and satiety |

| Cucumber Raita | 65 kcal | Hydration and probiotics |

Integrating these snacks allows for a caloric deficit meal plan that feels abundant. By replacing calorie-heavy items like fried samosas with roasted alternatives, an individual can save hundreds of calories daily.

Macro Management: Counting Macros for Body Composition

Counting calories determines the quantity of weight lost. Counting macros determines the quality of that weight loss. For those looking to lose fat while preserving muscle, protein intake is the most critical variable. Research recommends a protein intake of 1.4 to 2.2 grams per kilogram of body weight for active individuals.

Protein has several advantages. It has the highest thermic effect and provides the highest satiety. Fat should typically account for 0.3 to 0.5 grams per pound of body weight to support hormone production. The remaining calories are allocated to carbohydrates to fuel physical activity. This balance ensures that the body targets adipose tissue rather than breaking down muscle mass.

Designing a 1,500 Caloric Deficit Meal Plan

A 1,500-calorie daily intake is a common starting point for many looking for steady weight loss. A well-structured plan ensures nutritional needs are met despite reduced energy intake. Following a heart-healthy approach can lower the risk of cardiovascular disease.

A sample day might begin with a high-fiber breakfast of vegetable oats. Lunch can consist of a balanced plate of one whole-wheat roti, dal, and a large salad. Dinner should be lighter and protein-focused, such as grilled paneer or clear lentil soup. By adhering to this structure, individuals achieve a 500 to 750 calorie reduction per day.

Behavioral Strategies for Sustainable Weight Loss

The psychology of weight loss is more challenging than the physiology. Success is not determined by a single day of perfection. It is about what an individual does 90% of the time. Dietitians suggest that the “all or nothing” mentality causes failure. Instead, start with small changes, like walking for 10 minutes a day.

Another critical strategy is mindful eating. This involves paying attention to hunger cues rather than eating out of habit. Research shows that people who eat while distracted consume significantly more calories. Simple habits, such as using smaller plates and stopping when 80% full, help naturally regulate intake.

The Impact of Sleep and Stress on Metabolism

Metabolic health is also about sleep and stress. A study showed that individuals limited to five hours of sleep per night gained an average of 3 pounds over two weeks. Sleep deprivation impairs insulin response and increases cortisol.

Lack of sleep makes hyper-palatable snacks more tempting. “Catch-up” sleep on weekends does not reverse this damage. Similarly, chronic stress can tank the metabolism by putting the body into a “fight or flight” mode. This slows down fat oxidation. A successful strategy must prioritize a consistent sleep schedule and stress-reduction techniques.

Physical Activity: The Difference Between EAT and NEAT

While many focus on gym sessions (EAT), the energy burned during the rest of the day (NEAT) often has a larger impact. NEAT includes standing at a desk or walking to the car. Increasing NEAT is a sustainable way to boost the calorie deficit without exhaustion.

Exercise often fails to produce significant weight loss on its own because the body compensates by reducing movement later. However, exercise is essential for metabolic health because it reduces systemic inflammation. For those in a deficit, resistance training signals the body to maintain muscle mass, keeping the BMR higher.

The Planetary Health Diet: Aligning Longevity and Sustainability

Nutrition trends have shifted toward the Planetary Health Diet (PHD). This approach suggests that a diet healthiest for the human body is also healthiest for the planet. The PHD emphasizes plant-forward eating, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by limiting red meat.

Adhering to this pattern can reduce the risk of premature death by 30%. For weight management, the PHD provides a flexible framework that encourages whole plant foods. This alignment of personal wellness and environmental sustainability represents the future of dietary guidelines.

Navigating Plateaus and Metabolic Adaptation

Plateaus are a natural part of the journey. They occur when the calorie deficit shrinks as the body becomes smaller. When the scale stops moving, it is a signal that the current intake has become the new maintenance level.

To break a plateau, increase physical activity or reduce caloric intake by a small margin, such as 200 calories. It is also important to recognize “non-scale victories,” such as improved energy or better sleep. A “maintenance break”—eating at maintenance calories for a week—can reset hormonal signals like leptin.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a calorie deficit and how do I start? A calorie deficit occurs when you consume fewer calories than your body burns for energy. To start, calculate your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE) using your age, weight, and activity level. Subtract 300 to 500 calories from this number to set your goal.

Is a 500-calorie deficit enough to lose weight? Yes, a 500-calorie daily deficit is a safe target. It leads to a loss of about 0.5 kilograms per week. This allows for weight loss without extreme hunger or muscle depletion.

How can I calculate my calorie deficit accurately? The most accurate method is using the Mifflin-St Jeor equation to find your BMR and multiplying it by an activity factor. Alternatively, track your weight and intake for 10 days; if your weight is stable, your average intake is your maintenance level.

What are the best high protein low calorie snacks? Ideal snacks include roasted makhana, boiled chickpeas, paneer tikka, and greek yogurt. These options provide satiety and support muscle maintenance while keeping the total caloric intake low.

Can a calorie deficit affect my metabolism? Prolonged or extreme deficits can cause metabolic adaptation. To mitigate this, prioritize protein, include resistance training, and avoid cutting calories below your BMR.

Conclusion

The transition to a healthy weight requires an understanding of your biological context. While the fundamental driver is the calorie deficit, sustainability depends on food quality, sleep, and stress management. For professionals in high-stress environments, success lies in the quantification of habits and sustainable changes. View fitness as a lifelong commitment to biological stewardship. For more information on starting your journey, visit the National Institutes of Health (https://www.nih.gov). Ready to personalize your plan? Start here: https://dietdekho.com/form/.

BOOK YOUR APPOINTMENT