Table of Contents

- 1 The Biological Architecture of Human Metabolism

- 2 Defining Metabolic Adaptation and Adaptive Thermogenesis

- 3 The Indian Phenotype and Its Metabolic Implications

- 4 Metabolism and Medical Conditions: PCOS, Diabetes, and Thyroid

- 5 Nutritional Interventions: Using Indian Foods to Support Metabolism

- 6 Thermogenic Indian Spices and Metabolism

- 7 Physical Activity and the NEAT Factor

- 8 Psychological and Lifestyle Drivers of Metabolism

- 9 Strategic Approaches to “Reset” the Metabolism

- 10 Practical Meal Planning for the Indian Weight Loss Seeker

- 11 Understanding the “Plateau” as a Metabolic Signal

- 12 Conclusion: Navigating the Metabolic Journey

Direct Answer Block: Metabolism slows down during weight loss primarily due to a biological defense mechanism known as metabolic adaptation or adaptive thermogenesis. When you reduce calories, your body perceives a “famine” and responds by lowering its energy expenditure to preserve fat stores for survival. This process is driven by a drop in the hormone leptin, changes in thyroid function, and an increase in muscle efficiency. For Indians, this is often more pronounced due to the “thin-fat” phenotype, characterized by lower muscle mass and higher visceral fat. Managing medical conditions like PCOS, diabetes, and hypothyroidism further complicates this by adding hormonal resistance to the mix. To counter this, focusing on high-protein Indian foods (like dals, paneer, and soya), performing resistance training, and incorporating thermogenic spices (like turmeric and cinnamon) can help maintain a higher metabolic rate.

The Biological Architecture of Human Metabolism

Metabolism is often misunderstood as a static number or a “speed.” In reality, it represents the sum of every chemical reaction occurring within the body to maintain life. To understand why it slows down, it is first necessary to dissect the components of Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This complex system is comprised of the Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR), the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF), Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (EAT), and Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT).

The Resting Metabolic Rate is the energy required to keep vital organs like the heart, lungs, and brain functioning while at complete rest. It typically accounts for 60% to 75% of total energy expenditure. The Thermic Effect of Food represents the energy used to digest, absorb, and process nutrients. Protein has the highest TEF, requiring significantly more energy to process than fats or carbohydrates, which is a critical insight for those attempting to maintain metabolic speed during weight loss.

Physical activity is divided into EAT (planned exercise) and NEAT (unplanned movement like walking, fidgeting, or standing). During a weight loss journey, the body often subconsciously reduces NEAT to conserve energy, a subtle shift that can stall progress even if a person remains consistent with their gym routine. Understanding these components reveals that a “slow metabolism” is rarely a broken system but rather a highly efficient one that has adapted to a perceived lack of resources.

Defining Metabolic Adaptation and Adaptive Thermogenesis

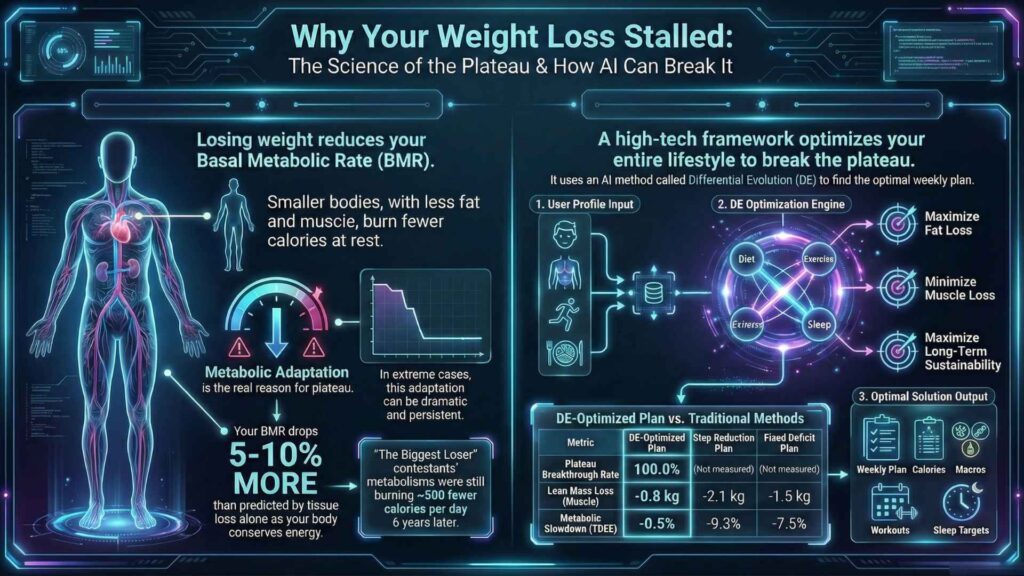

When an individual initiates a calorie deficit, the body begins a process of physiological recalibration. Metabolic adaptation is defined as the reduction in energy expenditure that exceeds what would be predicted by the loss of body mass alone. If a person loses 5 kilograms of weight, it is natural for their metabolism to drop slightly because there is less “mass” to support. However, adaptive thermogenesis describes the extra drop—the body’s active attempt to thwart further weight loss.

This adaptation is an evolutionary remnant from a time when food scarcity was a constant threat. The body does not realize that the calorie deficit is intentional; it simply detects a drop in energy availability and initiates a survival protocol. This protocol involves a coordinated response from the endocrine system, the nervous system, and cellular mitochondria.

The Role of Leptin and the Hypothalamic Response

The primary mediator of this slowdown is the hormone leptin, which is produced by adipose (fat) tissue. Leptin acts as a fuel gauge for the brain. When fat cells shrink during weight loss, leptin levels drop. This signal reaches the hypothalamus, which then orchestrates a reduction in energy expenditure across multiple systems. This includes lowering thyroid hormone production, increasing hunger signals, and making muscles more efficient so they burn fewer calories during movement.

Research conducted at institutions like the NIH and Harvard suggests that this “defense” of body weight is operant in both lean individuals and those in higher-weight bodies. The body essentially has a “set point” or a preferred weight range that it tries to maintain through these metabolic adjustments. In some studies, the metabolic rate was found to drop by as much as 15% to 18% beyond the expected decline, creating a significant barrier to sustained weight loss.

Table 1: Physiological Changes During Metabolic Adaptation

| System | Change Observed during Weight Loss | Impact on Metabolism |

| Hormonal | Decrease in Leptin, Thyroid (T3/T4) | Signals energy conservation to the brain |

| Neurological | Decreased Sympathetic Nervous System tone | Lowers RMR and heart rate |

| Muscular | Increased skeletal muscle work efficiency | Burns fewer calories for the same movement |

| Psychological | Increased Ghrelin (hunger hormone) | Increases drive to eat, making adherence difficult |

| Metabolic | Decrease in 24-hour energy expenditure | Can drop by 150−400 kcal/day beyond mass loss |

The Indian Phenotype and Its Metabolic Implications

The Indian population faces unique metabolic challenges that are often not addressed in Western-centric health models. The “thin-fat” phenotype is a well-documented phenomenon where individuals in the Indian subcontinent may have a normal BMI but a high percentage of visceral fat and low muscle mass. This profile is particularly prevalent among urban professionals and is a major driver of the high rates of Type 2 Diabetes and metabolic syndrome in India.

Visceral fat, or the fat stored around internal organs, is metabolically harmful. It releases pro-inflammatory cytokines that interfere with insulin signaling, leading to insulin resistance. For an Indian seeker of weight loss, this means that even a modest amount of weight gain can have severe metabolic consequences. Conversely, the lack of skeletal muscle means the baseline RMR is often lower than what standard global calculators might suggest, as muscle tissue is more metabolically active than fat tissue.

ICMR Guidelines and Metabolic Thresholds

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has recognized these differences by establishing lower BMI cut-offs for heavier weight and higher weight in India. While a BMI of 25 kg/m2 is considered the threshold for heavier weight globally, for Indians, this marker begins at 23 kg/m2. This reflects the clinical reality that Indians develop metabolic diseases at lower levels of adiposity than Caucasians.

Table 2: BMI and Body Composition Criteria for Asian Indians

| Parameter | Normal Range | Heavier weight | Higher weight |

| BMI | 18.5−22.9 kg/m2 | 23−24.9 kg/m2 | ≥25 kg/m2 |

| Waist Circumference (Men) | <90 cm | ≥90 cm | N/A |

| Waist Circumference (Women) | <80 cm | ≥80 cm | N/A |

| Body Fat % (Men) | N/A | >25% | N/A |

| Body Fat % (Women) | N/A | >30% | N/A |

This unique phenotype means that when an Indian professional attempts a standard calorie-restricted diet, they may experience metabolic adaptation sooner and more aggressively because their “metabolic reserve”—their muscle mass—is already limited.

Metabolism and Medical Conditions: PCOS, Diabetes, and Thyroid

For those managing specific medical conditions, the metabolic slowdown is not just a side effect of dieting but a core component of their disease pathology. Understanding these intersections is vital for creating a sustainable weight loss plan.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS/PCOD)

PCOS is an endocrine disorder that affects millions of Indian women. It is characterized by an imbalance of reproductive hormones, including elevated levels of androgens (male hormones) and insulin. Insulin resistance is a hallmark of PCOS, present in up to 70% of cases regardless of weight. High insulin levels act as a signal for the body to store fat, particularly in the abdominal area, and make it extremely difficult for the body to access stored fat for energy.

Furthermore, women with PCOS often have an altered LH/FSH ratio, which can suppress the metabolism further. Studies have shown that PCOS is also strongly associated with subclinical hypothyroidism, which compounds the metabolic slowdown. For these women, weight loss requires more than just “eating less”; it requires strategies that specifically target insulin sensitivity and hormonal balance.

Hypothyroidism and the Metabolic Thermostat

The thyroid gland is the master controller of metabolism. It produces T4 and T3 hormones that dictate how fast every cell in the body burns energy. In hypothyroidism, the “engine” is effectively turned down. Symptoms of a slow metabolism due to thyroid issues include persistent fatigue, cold intolerance, and unexplained weight gain.

Crucially, dieting itself can suppress thyroid function. When the body detects a severe calorie deficit, it reduces the conversion of T4 to the active T3 hormone to save energy, a key component of metabolic adaptation. For patients already dealing with an underactive thyroid, this can make weight loss feel nearly impossible without medical intervention and a carefully structured diet.

Diabetes and Metabolic Flexibility

Metabolic flexibility is the ability of the body to switch between burning glucose (sugar) and burning fatty acids (fat) based on availability. In Type 2 Diabetes and prediabetes, this flexibility is lost. Because of insulin resistance, the body remains in a “glucose-burning” state even when energy is needed, leading to hunger and fatigue. When people with diabetes try to lose weight, the metabolic slowdown is exacerbated by the body’s inability to efficiently burn its fat stores, leading to a loss of lean muscle mass as the body seeks alternative energy sources.

Nutritional Interventions: Using Indian Foods to Support Metabolism

While metabolic adaptation is a natural response, it can be mitigated through strategic nutrition. The ICMR-NIN 2024 guidelines emphasize that a balanced diet for Indians must focus on quality proteins and the reduction of refined carbohydrates.

The Role of Protein in Metabolic Health

Protein is the most critical nutrient for protecting the metabolism during weight loss. It provides the building blocks for muscle tissue and has a high Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). By increasing protein intake, individuals can signal their body to preserve muscle mass even in a calorie deficit.

For the Indian vegetarian palate, achieving adequate protein requires mindful planning. Traditional sources like dals and pulses are excellent but must be paired with other proteins to ensure a complete amino acid profile.

Table 3: Protein-Rich Indian Foods and Metabolic Benefits

| Food Item | Protein Content (per 100g) | Metabolic Benefit |

| Soya Chunks | 52 g | Complete protein, promotes fat oxidation |

| Paneer (Low-Fat) | 18−20 g | Casein protein provides slow-release energy and satiety |

| Greek Yogurt / Hung Curd | 10 g | Probiotics support gut health and insulin sensitivity |

| Lentils (Moong/Urad Dal) | 7−9 g (cooked) | Fiber helps stabilize blood sugar levels |

| Chickpeas (Chana) | 15 g (cooked) | High resistant starch supports a healthy gut |

| Ragi (Finger Millet) | 7.3 g | High calcium and iron support thyroid function |

The Power of Millets and Ancient Grains

The ICMR recommends that at least half of the cereal intake should come from whole grains or millets. Grains like Bajra (Pearl Millet), Jowar (Sorghum), and Ragi have a lower Glycemic Index (GI) than white rice or refined wheat. This means they digest slowly, providing a steady release of energy and preventing the insulin spikes that drive fat storage and metabolic slowdown.

Thermogenic Indian Spices and Metabolism

Indian kitchens are a treasure trove of “metabolism boosters.” Traditional spices do more than add flavor; they contain bioactive compounds that can influence metabolic rate and digestion.

Table 4: Metabolic Properties of Traditional Indian Spices

| Spice | Bioactive Compound | Metabolic Action |

| Turmeric (Haldi) | Curcumin | Reduces inflammation, potentially aiding fat loss |

| Cumin (Jeera) | Thymol | Stimulates digestive enzymes, improves fat breakdown |

| Cinnamon (Dalchini) | Cinnamaldehyde | Helps regulate blood sugar and insulin levels |

| Ginger (Adrak) | Gingerol | Stimulates thermogenesis and increases satiety |

| Fenugreek (Methi) | Galactomannan | Curbs hunger and improves insulin sensitivity |

| Black Pepper | Piperine | Improves nutrient absorption and metabolic speed |

Incorporating these spices into daily meals or morning drinks (like Jeera-Ajwain water) can provide a gentle metabolic “nudge.” For example, Ajwain (carom seeds) helps reduce bloating and improves gut motility, which is often sluggish in those with a slow metabolism.

Physical Activity and the NEAT Factor

Exercise is the only variable of energy expenditure that we can fully control. However, the type of exercise matters immensely when fighting metabolic adaptation.

Strength Training vs. Cardio

While cardio (like brisk walking or jogging) is excellent for cardiovascular health, it does little to change the baseline metabolic rate. Strength training, on the other hand, builds muscle mass. Because muscle tissue burns more calories at rest than fat tissue, increasing muscle mass is like upgrading your body’s “engine” to a larger size.

For Indian women, who often fear “bulking up,” it is important to understand that resistance training is the most effective way to lower abdominal fat and improve insulin sensitivity in conditions like PCOS.

The Importance of NEAT for Professionals

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) accounts for a massive portion of our daily calorie burn. For busy professionals who sit for 8-10 hours a day, NEAT is often non-existent. The body responds to this lack of movement by further slowing down metabolic processes.

Practical ways to increase NEAT in an Indian context include:

- Walking while on phone calls.

- Taking the stairs instead of the lift in office buildings.

- Performing “micro-walks” of 10 minutes after every meal.

- Standing up and stretching every 30 minutes to reset insulin sensitivity.

Psychological and Lifestyle Drivers of Metabolism

Metabolic health is not just about calories and movement; it is deeply tied to how we live, sleep, and manage stress.

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm

The ICMR highlights the importance of maintaining a circadian rhythm linked to sunrise and sunset. Sleep deprivation (less than 7-8 hours) is a major metabolic disruptor. It increases cortisol levels and decreases the body’s ability to manage blood sugar. For those trying to lose weight, a lack of sleep can lead to muscle loss and an increase in cravings for sugary, high-calorie foods.

Stress and the Cortisol Connection

Chronic stress is a silent metabolism killer. High levels of cortisol signal the body to store fat around the midsection (visceral fat) and can interfere with thyroid hormone production. In India, workplace stress and societal pressures are significant factors. Incorporating stress-reduction techniques like Yoga, Pranayama, or simple deep breathing can help lower cortisol and support metabolic efficiency.

Strategic Approaches to “Reset” the Metabolism

If you have hit a weight loss plateau, the answer is rarely to eat even less. Doing so may only worsen metabolic adaptation. Instead, strategic interventions can help “remind” the body that it is not starving.

Refeeds and Diet Breaks

A diet break is a period of 1-2 weeks where you eat at your “maintenance” calories (the amount needed to stay at your current weight) rather than at a deficit. Research has shown that these breaks can help normalize hormone levels like leptin and thyroid, making it easier to lose weight when you return to the deficit.

Reverse Dieting

After reaching a weight loss goal, many people make the mistake of immediately returning to their old eating habits, leading to rapid weight regain. Reverse dieting involves slowly increasing calories back to maintenance over several weeks. This allows the metabolism to adapt upward, effectively increasing the amount you can eat without gaining weight.

Practical Meal Planning for the Indian Weight Loss Seeker

A successful diet for metabolism must be culturally relevant and sustainable. Here is a synthesis of the best practices for an Indian context.

Table 5: Sample Metabolic Support Meal Plan (Vegetarian)

| Meal Time | Food Options | Metabolic Rationale |

| Early Morning | Warm water with Lemon/Methi seeds + 5 Soaked Almonds | Hydration and early insulin stabilization |

| Breakfast | Paneer Bhurji with 1 Multigrain Roti OR Besan Chilla with Curd | High protein to kickstart the thermic effect |

| Mid-Morning | 1 Apple or Guava + 1 cup Green Tea | Fiber and antioxidants to support fat oxidation |

| Lunch | 1 cup Dal + 1 cup Veg Sabzi + 1 cup Curd + small portion Brown Rice/Millet | Balanced macronutrients with slow-digesting carbs |

| Evening Snack | Roasted Chana OR Makhana + Handful of Walnuts | Healthy fats and protein to prevent evening crashes |

| Dinner | Moong Dal Khichdi with lots of veggies OR Grilled Paneer/Tofu salad | Lighter meal to align with circadian rhythms |

| Before Bed | Turmeric Milk (Haldi Doodh) with a pinch of Cinnamon | Anti-inflammatory and promotes restful sleep |

Understanding the “Plateau” as a Metabolic Signal

A weight loss plateau is not a failure; it is a sign that your body has successfully adapted to your current calorie level. When the calories you burn equal the calories you eat, weight loss stops. To break a plateau, you have two choices: increase energy expenditure (move more) or decrease intake (eat less), but both must be done cautiously to avoid further adaptation.

The most effective way to break a plateau is often to increase movement through NEAT and strength training while keeping protein high, rather than drastically cutting calories further. This approach preserves muscle mass and ensures that the weight being lost is fat, not vital metabolic tissue.

Metabolic adaptation is a formidable but predictable obstacle in the weight loss journey. By understanding the biological signals of leptin, the unique challenges of the Indian “thin-fat” phenotype, and the impact of medical conditions like PCOS and thyroid disorders, individuals can move away from restrictive, “crash” dieting and toward a sustainable, research-backed lifestyle.

The key to a high-functioning metabolism in the Indian context lies in the preservation of muscle through protein and strength training, the use of traditional thermogenic spices, and a commitment to movement and recovery. Weight loss is a marathon, not a sprint, and respecting the body’s metabolic engine is the only way to ensure long-term success.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I tell if my metabolism has slowed down? Common signs include hitting a weight loss plateau despite consistent dieting, feeling unusually cold, persistent fatigue even with sleep, and thinning hair or dry skin.

Q2: Is it possible to “fix” a broken metabolism? The metabolism is rarely “broken”; it is simply “adapted.” You can reverse this adaptation through reverse dieting, increasing muscle mass via strength training, and ensuring adequate sleep and stress management.

Q3: Are some Indian foods better for metabolism than others? Yes. Foods high in protein and fiber, such as soya chunks, paneer, dals, and millets (like Ragi and Bajra), are superior for metabolic health compared to refined carbs like white rice and maida.

Q4: Should I skip breakfast to speed up weight loss? Research often suggests that a high-protein breakfast helps “reset” the metabolism and prevents overeating later in the day. Skipping breakfast can sometimes lead to a slower RMR in the long run.

Q5: Can spices alone cause weight loss? No. While spices like turmeric, cinnamon, and ginger have thermogenic properties that support metabolism, they must be used as part of a balanced diet and active lifestyle to be effective.

Disclaimer: This blog post was written to help you make healthier food choices altogether. So, be aware and take care. The important thing to consider is your health before starting a restrictive diet. Always seek advice from a doctor or dietitian before starting if you have any concerns.

BOOK YOUR APPOINTMENT

Dr. Ritika is a nutrition and lifestyle expert with 2+ years of experience, helping clients manage weight and health through practical, personalized diet plans.